Dr. Geek: The Fractured Nature of Fandoms

Here we are in the United States of America, having just gotten past yet another July 4th holiday weekend, where you are required to show your official fandom as being an American patriot through draping yourself and your belongings with the flag, eating and drinking as much as you can with the people you love, and crowing over the explosions of symbolic rockets red glare. As it is a holiday about what it means to be a fan, I thought we would delve into some interesting thoughts my friends and I have been sharing regarding how fandom works. And, as these are only initial thoughts, I would love to hear back from all of you to see if you agree with how we are characterizing fans.

Now, first and foremost, let it be said that I think these thoughts we have been sharing could apply to any fandom that exists in the world. We have been speaking in particular to pop culture fandoms, but it could apply just as well to sports fans, patriots, and even religious followers. I say this because at the core of fandom — at the core of being a fan — is this affection a person has towards some object, which could be anything in reality. If you love trying new foods, then you are a foodie. If you love Catholicism, then you are a fan of Jesus Christ. If you are in a fantasy football league, then you are a sports nut. We have all kinds of terms for these various peoples, but at their core is their affection, which can border on obsession, with someone or something in their lives that in some way gives meaning to their lives — from bringing joy to bringing hope to bringing company. Being a fan of something may be just a condition of being a human.

With that said, if you are not a member of a particular fandom — if you do not have the same affection of those that do — then you may have the tendency to think fandoms as monolithic communities of people who get along just because they are fans. As an outsider, we look at a group and see it holistically, where the differences between people do not matter so much because of how unified they are with the commonality, the affection they all share. As outsiders, we tend to see a fandom and label them as Whovians (Doctor Who fans), Trekkies (Star Trek fans), Twihards (Twilight fans), foodies, Catholics, sports nuts, etc. We focus on that overwhelming characteristic and stereotype all members of that fandom as being the same because of their commonality. We often do not feel the need to look deeper, to understand those within the fandom for their differences, for what makes them unique. We see them as the “Other”, not like us. Given the fandom, and our stance towards it, we may start giving them other labels: stupid, obsessive, childish, immature.

We may think that the one defining characteristic is enough to understand exactly how the entire fandom will act, what their thoughts, feelings, attitudes, behaviors are. We may make the logical assumption that: given the commonality they share, they must share other characteristics as well. As scholars, we study a sample of Whovians, and argue it extends to the entire fandom. As marketers, we determine the buying habits of several foodies, and see it extending to all foodies. As politicians, we determine how one Protestant congregation will vote and believe all followers will do likewise.

However, to reason as such is a logical fallacy. It is a hasty generalization, a leap to conclusion, to assume to know all about a large group just due to one or two shared traits. Being a part of a fandom does not mean that all members are homogeneous: they do not all conform, have their identities scrubbed in order to promote sameness. Each member is a unique human being, full of contradictions within himself and amongst his fellows. To label and assume is to downplay their individual uniqueness, which they bring to the fandom and make it such an interesting experience.

Bugs me that the term “fans” applies to ALL fans. There should be more specific categories. Like Super-Awesome Fans… and Lunatic-Assholes.

— Dan Slott (@DanSlott) July 4, 2013

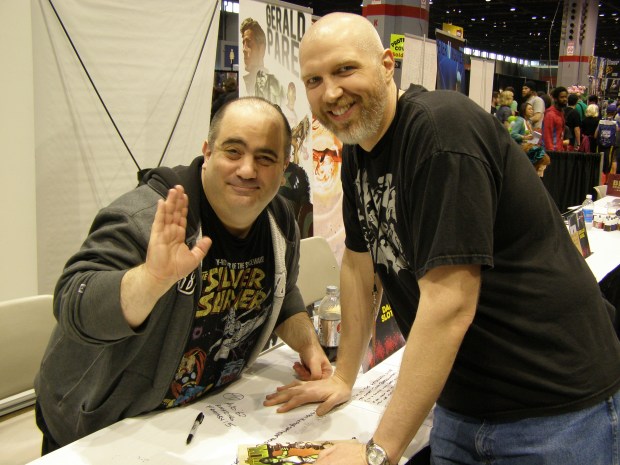

Dan Slott is a comic book writer, perhaps currently best known for writing first the Amazing Spider-Man and then Superior Spider-Man comics in which *SPOILER* he sorta, kinda kills off Peter Parker (not really?). He is also a Whovian. We know this because we met him at the 2012 C2E2.

The Twitter post from him recently quite nicely ties in with what my colleagues and I have been discussing: we need to stop looking at fandoms as being monolithic. We need to understand, appreciate, and study the variations that occur within fandoms due to individual differences. Doing so would better help our understanding of those fandoms, and what it means to be a fan, as well as provide us with new veins of study, such as how do people get along within and amongst fandoms.

Fandoms are not monolithic communities but fractured, containing various factions held together by that commonality they share. This realization led me to consider how some behaviors I see fans (and myself) engaging in results in these fractures. And, right now, I see the fractures occurring on three dimensions. And if you know your Cartesian coordinates from trigonometry and calculus, I am thinking of the dimensions that create three-dimensional space. Because, after all, I am a science fan.

The first dimension to speak of is the vertical one, your y-axis. This is a dimension that separates fans from one another based on assumptions of superiority. These are the fans who might consider themselves better than other fans within the fandom for any number of reasons. “I was here first.” “I was here before it was cool.” “I know more than you.” These are the fans who may look down from their assumed high perch in the fandom on those newcomers or less ardent or, as has become an issue lately, may not even be true fans, as in “fake geek girls“. Consider the fans you know who share your affection, and you will most likely find at least one who is playing this positioning game of better than/less than.

Courtesy of Jason Margos: http://jasonmargos.tumblr.com/post/35799349261/real-geek-girl-ink-on-paper-digital-color-font

The second dimension is the horizontal x-axis. Along this dimension you will find clusters of fans within the fandom who differ from one another in terms of their affection: what aspect of the object they love and how and why, and how and why they express their affection. You see these fans who form factions based on different shipping: who they believe should end up in a relationship in the canon. They identify their specific interest in the object through labels that represent who they ship: And so you end up with: Harry/Hermione, Buffy/Angel, 10th Doctor/Rose, Spock/Kirk. And with that last pairing, you get an even more specific subset within fandoms: the slashers, those who seek to develop homosexual relationships for heterosexual characters. These slashers then are pitted against others in the fandom who may be adamantly non-slashers, to the point of wishing to segregate themselves from such activities. Along this dimension, we can see many different audiences for the object all within one fannish umbrella.

The final dimension is not necessary a fracture within a specific fandom, but it is a comment on fandom and fans overall. This is the diagonal z-axis, that finally makes for the 3D space. Here we are looking at the concept of being inside/outside the fandom. We are considering fandoms as they buttress one another, stacking up to create a universe of fandoms that are more or less connected from each other: the further you move from one fandom to others, then the less alike they will be based upon their objects of affection. Star Trek and Star Wars are more alike than Star Trek and Twilight or Star Trek and The Green Bay Packers. And yet, sometimes those fandoms that truly buttress one another feud, saying you cannot be a fan of both, that one is better than the other, that they are more dissimilar than similar. No doubt this is just the act of identity defense: of the need we all have to develop and maintain a feeling of self-worth.

But we also see people who will buttress a fandom by being its polar opposite: an anti-fandom. In these instances, there may be people whose actions are overtly critical of the fandom, the fans, the object of affection they all share. They share the focus on the object, but they oppose one another in the orientation towards it. While newer in terms of the pop culture fandoms, this is not really a new idea for other types of fandoms. After all, sports teams thrive on fan rivalry, and religious wars have been fought because of different orientations to the same object of affection.

Now, these are how I see fandoms breaking down and relating to one another. It is all just pure thought and speculation now, based on observations and experiences. I think there is use in looking at fandoms this way because it helps us see the complexities that come from when people interact with one another. And if we can see these complexities, then perhaps we can do something to help fans within and across fandoms communicate and interact with one another. So that we can take care of the derogatory labeling of women as “fake geek girls” or the assumption that cosplaying is consent for sexual harassment (here’s a hint: it’s not!). We can deal with the vitriol spilled online against fans, anti-fans, slashers, and more. We can find ways of accepting that we all like different objects, or we all like the same object in different ways — and that what matters is that we have the heart and soul to like anything in the first place.

We need to recognize that being a fan is more important than what we are a fan of.

Pingback: Dr. Geek: The Fractured Nature of Fandoms | Playing, With Research

Pingback: Equestria Girls: Displeasure Among Bronies | Playing, With Research

Pingback: “I AM the Doctor.”: The Historical Trajectory of Doctor Who | Playing, With Research

Pingback: Fractured Fandom | Playing, With Research

Pingback: Polysemic rhetorical flexibility and non-traditional audience reception in Doctor Who | Seems Obvious to Me